Why Zero-Sum Thinking Falls Short

Many of us see the world as a fixed pie: if someone wins, another must lose. That zero-sum intuition shows up everywhere, from workplace promotions to debates over trade and technology. Yet most evidence suggests real economies and communities grow rather than split a fixed pot. Data on global poverty, insights from competition policy, and everyday examples of collaboration all point toward a more hopeful picture, one where smart design and shared effort expand value for many. Below we explore what zero-sum truly means, how the pie actually grows, and practical ways to recognize win-win opportunities in your own life.

What zero-sum really means

A zero-sum game is any situation where one person's gain equals another person's loss. Think of poker or a championship trophy with a single winner. If you take a bigger slice, I end up with less. In practice, many everyday exchanges look nothing like that. Learning a new skill from a colleague doesn't diminish the teacher; sharing a recipe leaves both people with the same dish. Trade, innovation, and knowledge-sharing often create surplus value so both sides walk away better off than when they started.

One powerful way to move beyond zero-sum outcomes is to build systems where contributors share in the upside. When ownership and rewards are distributed across participants, people have stronger reasons to collaborate instead of hoard. The Marpole whitepaper shows how decentralized, modular platforms implement Co-Ownership principles so each new participant adds value to the network rather than competing for a fixed slice, aligning incentives across contributors and encouraging collaborative growth over zero-sum rivalry.

The difference between zero-sum and positive-sum frames what we consider possible. Zero-sum logic says every improvement for someone comes at someone else's expense. Positive-sum logic recognizes that education, invention, and cooperation expand the total so more people can benefit at once. That shift in framing matters because it changes how we design policies, companies, and communities. The next sections bring data, policy examples, and collaboration strategies to show why and when the pie grows.

The data: the pie keeps growing

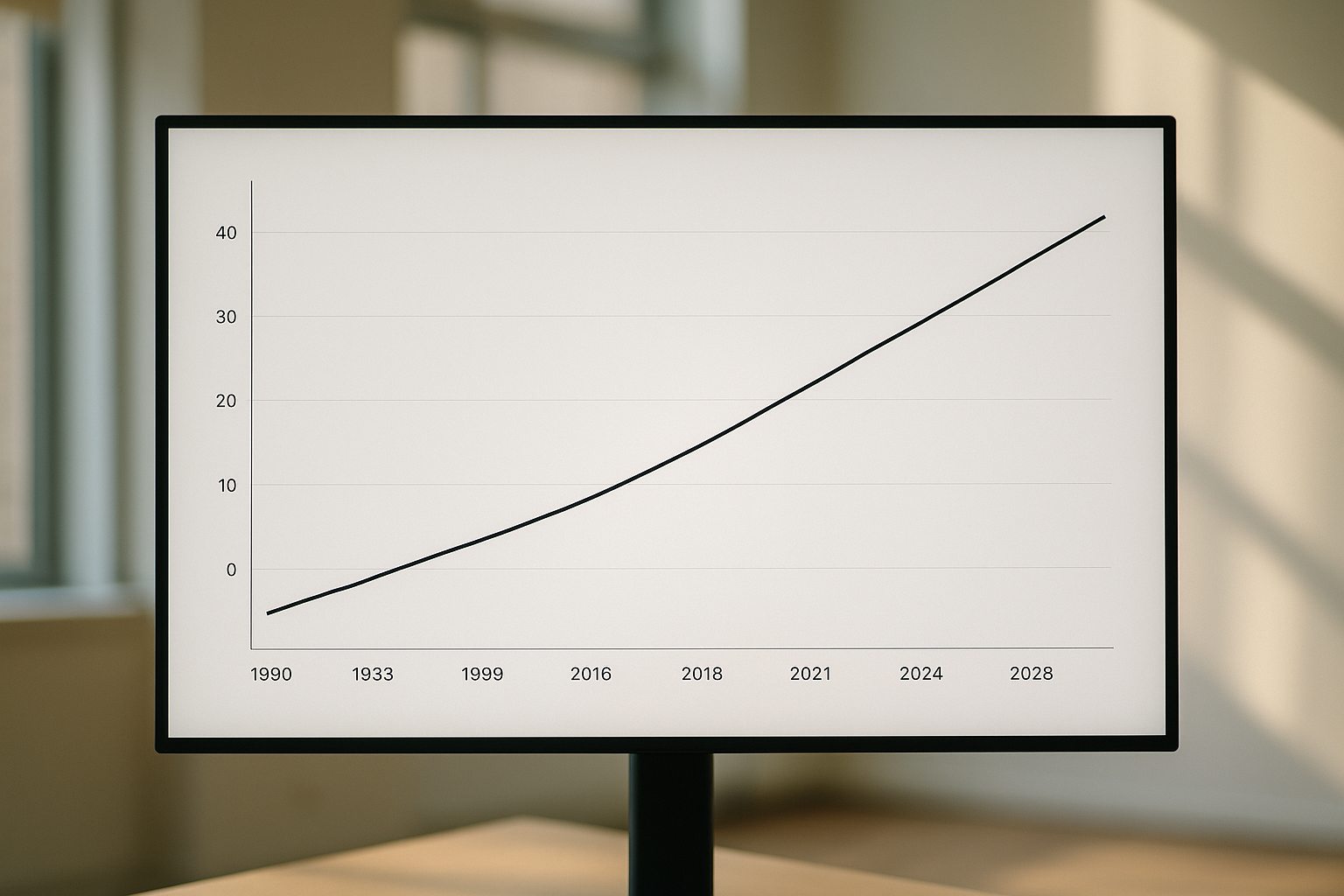

Global extreme poverty rates offer one of the clearest positive-sum narratives. In 1990 roughly 38 percent of the world's population lived on less than two dollars a day. By 2024 that share had fallen to around 8.5 percent. The decline did not come from taking resources from one region and giving them to another; it emerged from productivity gains, technology diffusion, better institutions, and trade that lifted millions out of destitution. The World Bank projections suggest the trend continues, with further reductions in extreme poverty expected through 2025.

Technological improvements make goods cheaper and more accessible. When a farmer adopts better seeds or a factory invests in automation, consumers often benefit from lower prices while producers gain from higher efficiency. Both sides can win. The same dynamic unfolds in services: better logistics mean faster delivery and lower costs, and digital platforms reduce transaction friction so buyers and sellers meet more easily. That multiplies opportunities rather than dividing a fixed stock.

Broad-based growth depends on open access to education, infrastructure, and credit, not on redistribution alone. When more people gain the tools to produce value, whether through schooling, internet access, or financial services, the total pie expands. Over three decades the world economy has grown severalfold in real terms, and hundreds of millions have joined the global middle class. That kind of progress is incompatible with a strict zero-sum view; the gains are too large and too widespread to explain by mere transfers.

Why rivalry can grow the pie

Competition often feels adversarial, yet healthy rivalry pushes innovation, lowers prices, and improves quality. Firms racing to build a better product create choices that did not exist before. Consumers gain access to new features, and the winning company earns market share without necessarily taking it from a fixed pool of demand. New demand can emerge when a product becomes cheaper or better.

Regulators recognize that protecting competition is essential to avoid zero-sum traps. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission issued a 2024 joint statement on enforcement priorities in AI markets, emphasizing the need to deter exclusionary tactics and keep markets open to new entrants. When dominant players lock competitors out through tying, bundling, or exclusive agreements, markets risk becoming zero-sum: one firm's gain comes from foreclosing rivals rather than expanding value. Clear competition rules aim to preserve the positive-sum dynamic where multiple firms can grow by serving customers better.

Open markets lower barriers to entry so new ideas can reach consumers. A startup can challenge an incumbent if it offers a real improvement in cost, quality, or convenience. That dynamic means the total value available to customers keeps rising. Innovation is not about redistributing a fixed pot but about making the pot bigger. The same principle applies in labor markets: when workers can move to better opportunities, firms compete on compensation and working conditions, lifting standards industry-wide rather than pushing one group down to lift another.

Collaboration that multiplies value

Teams that pool knowledge and share rewards can achieve results no single person could replicate. Co-creation models combine diverse skills and perspectives, producing insights or products more valuable than the sum of individual contributions. When contributors see tangible rewards like revenue shares, credit, or governance rights, they invest effort and creativity because their success aligns with the group's success.

Participatory governance structures help collaborations scale without fracturing. If decisions about direction and resource allocation are made transparently and contributors have a voice, the collaboration stays resilient even as it grows. Decentralized and modular architectures support this dynamic by letting many people build components that interoperate without central bottlenecks. Each contributor adds a module or service that others can use, expanding the ecosystem's capacity without displacing existing participants.

Cross-border and multi-stakeholder programs illustrate how partnerships create new value instead of reallocating a fixed stock. European Union small and medium enterprise initiatives, for example, fund joint research and development projects where companies, universities, and public agencies share costs and results. Those collaborations generate intellectual property, jobs, and products that would not have existed if each party had worked alone. Shared upside makes cooperation rational rather than altruistic, turning potential rivals into partners who expand the market together.

When zero-sum logic does apply

Not every contest can escape zero-sum constraints. A single championship trophy, a fixed number of university seats, or a unique piece of land can only go to one party. In those cases one person's gain truly is another's loss, at least in the short run. Recognizing these situations helps us apply the right strategies: pure competition where scarcity is real, and cooperation where capacity can expand.

Short-term scarcity often feels immovable, but investment and innovation can relax constraints over time. A city with limited housing faces zero-sum pressure today, with every new tenant displacing someone else, yet building more units expands supply so more people benefit. Similarly, a saturated job market looks zero-sum until new industries or roles emerge. The key is to ask whether the constraint is structural or temporary, and whether policy or capital can unlock additional capacity.

Competition enforcement plays a role here too. When incumbents use exclusionary tactics to keep rivals out, markets become artificially zero-sum even if the underlying demand could support many players. The FTC's 2024 focus on deterring foreclosure and tying in technology markets aims to prevent that outcome, preserving space for new entrants to grow the total rather than fight over a fixed pie. Clear rules and vigilant enforcement keep competition positive-sum by ensuring that winning depends on creating value, not blocking others.

Simple ways to think positive-sum

Spotting win-win opportunities starts with adjusting a few mental habits. First, zoom out on time horizons. What looks like a fixed pot today may expand as you and your partners learn, scale, or attract new resources. Learning effects and network effects compound over years, revealing value that a short snapshot misses. Second, split value into multiple dimensions like price, quality, delivery speed, service, and access. When you improve more than one dimension, deals become easier because both sides gain on different fronts. A supplier who cuts lead times while you commit to steady volume creates a win-win even if the price stays flat.

Third, design agreements with shared upside so partners benefit when they help you succeed. Equity stakes, revenue shares, and performance bonuses align incentives and turn potential adversaries into collaborators. When someone's reward grows with the total pie rather than a fixed split, cooperation becomes self-interested rather than charitable. Fourth, track broad indicators to stay grounded in the fact that progress is possible. Real-world data shows millions moving out of poverty and entire industries emerging from invention, evidence that zero-sum intuitions often mislead.

Finally, ask whether a barrier is natural or artificial. If scarcity comes from regulation, gatekeeping, or lack of information, policy changes or technology can unlock new supply. If scarcity is inherent, like a single award or a unique asset, then competition is appropriate, but even there you can look for ways to expand the category over time, such as creating more awards or developing substitutes. With practice these habits become second nature, helping you spot collaborative paths that zero-sum instincts would miss.

What to watch next

Policy makers worldwide are paying closer attention to how competition and collaboration shape economic outcomes, especially in fast-moving sectors like artificial intelligence. Clear guardrails aim to keep markets open to new entrants so innovation remains positive-sum: multiple firms can grow by serving customers better rather than locking each other out. Expect continued scrutiny of tying, bundling, and exclusive agreements that risk turning vibrant markets into zero-sum contests over fixed turf.

New co-creation and shared-value models are emerging that broaden who participates in growth and who benefits from it. Platforms that distribute ownership or governance rights to contributors can align incentives and sustain collaboration at scale. These structures move beyond traditional employment or licensing by giving participants a stake in the ecosystem's success, turning more transactions into partnerships. Watch for examples in open-source software, decentralized networks, and cooperative business models that blend competition with shared rewards.

Finally, keep an eye on indicators and open ecosystems that lower barriers so more people can contribute. Whether it is open data standards, interoperable platforms, or public investment in infrastructure, policies that reduce friction and gatekeeping tend to expand the pie. The more individuals and organizations can experiment, share, and build on each other's work, the less likely we are to fall into zero-sum traps. Positive-sum outcomes are not automatic, but they become more likely when systems reward collaboration and keep doors open to newcomers.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a zero-sum game?

A zero-sum game is any scenario where one participant's gain exactly equals another participant's loss, so the total value stays constant. Classic examples include poker, where every dollar won comes from another player's stack, or a single prize where one winner means everyone else loses. The defining feature is that no new value is created; participants are merely redistributing a fixed pot.

Are most real-world markets zero-sum?

No. Most real-world markets are positive-sum because trade, innovation, and productivity improvements create new value rather than just reallocating what exists. When a company invents a better product or a farmer adopts more efficient techniques, consumers gain access to better goods and the producer earns more profit, often without anyone losing. Competition can drive firms to expand the total pie by lowering costs, improving quality, or opening new categories that did not exist before.

What data shows the pie can grow?

Global poverty trends offer clear evidence. Extreme poverty fell from about 38 percent of the world population in 1990 to roughly 8.5 percent by 2024, meaning hundreds of millions of people gained resources that were not simply taken from others. Real global GDP has grown severalfold over the same period, confirming that economic progress can be broadly shared rather than zero-sum.

How can I avoid zero-sum thinking day to day?

Start by extending your time horizon so you see how learning and scale effects compound value. Break value into multiple dimensions like price, quality, and delivery so you can find trades where both sides win on different fronts. Design partnerships with shared rewards like equity, revenue shares, or milestone bonuses so your success helps your partners succeed too. Finally, check whether scarcity is natural or artificial; many barriers can be lowered through better information, technology, or policy, turning apparent zero-sum contests into opportunities for mutual gain.